...so please, please, please do not withhold from your thesis statement the point of the essay.

Do not write that there is a deeper cause for something without saying immediately what that cause is.

Do not write that the story has a theme without saying immediately what that theme is.

Please give away the end.

How to Write for Dr. Bates - content, structure, format

Thursday, May 8, 2014

Sunday, April 27, 2014

Don't You Even... (dealbreakers/grade-destroyers)

There are a number of frustrations that come with grading essays. And, contrary to legend, not everything about grading essays is frustrating. For example, I get to read my students' ideas that they either didn't bring up during discussion or hadn't developed until they sat down to write the essay - that's my favorite part. There are new, interesting ideas in each stack of essays. There is some great writing to be enjoyed for its own sake.

Of the frustrations that come with grading essays, most are small annoyances. The vast majority of problems in an essay are forgivable mistakes that might ding the grade, especially if they pile up, but which are the understandable result of a student with a number of classes to juggle who got only one appointment with the Writing Center and only one or two revisions done before the deadline. An unintentional fragment (big deal, it happens). An organizational structure that stumbles (it made sense at the time). Predictable and/or not very thorough research (you're not that into the class, I understand). I wish these essays were better, and the grade won't be anything to write home about, but whatever, they show some effort and the ideas come across in the end.

But some frustrations are so huge, so massive, that they feel like an insult to my time and my intelligence. These "What Were You Thinking???" essays truly make me wonder if the student even begins to understand how uncool it is to totally waste the time of the person who determines the course grade.

If you want me to get so angry/frustrated while I am grading your essay that I have to get up and walk around for a minute so I can clear my head, do any combination of the following*:

Of the frustrations that come with grading essays, most are small annoyances. The vast majority of problems in an essay are forgivable mistakes that might ding the grade, especially if they pile up, but which are the understandable result of a student with a number of classes to juggle who got only one appointment with the Writing Center and only one or two revisions done before the deadline. An unintentional fragment (big deal, it happens). An organizational structure that stumbles (it made sense at the time). Predictable and/or not very thorough research (you're not that into the class, I understand). I wish these essays were better, and the grade won't be anything to write home about, but whatever, they show some effort and the ideas come across in the end.

But some frustrations are so huge, so massive, that they feel like an insult to my time and my intelligence. These "What Were You Thinking???" essays truly make me wonder if the student even begins to understand how uncool it is to totally waste the time of the person who determines the course grade.

If you want me to get so angry/frustrated while I am grading your essay that I have to get up and walk around for a minute so I can clear my head, do any combination of the following*:

- Use Sparknotes or Cliffsnotes or Wikipedia as a reference. -- I know I said in class and on the syllabus to use them as reading guides on difficult texts, but I also said very clearly that they are not research and are never, ever, ever to be used as reference in an essay

- Turn in an essay that is half of required minimum length

- Use no organizational structure whatsoever, so that the essay is more or less a string of vaguely related sentences. Occasionally hit "enter" and "tab" to create the illusion of a new paragraph. Begin with a wandering, sloppy introduction that isn't really about anything in particular but has a definition (or two) and maybe a reference to pop culture

- Quote absolutely nothing from the primary text (Yes, the actual text you're writing the essay about), but rather discuss it generally, and maybe throw in some quotes from a one or two of the seven secondary sources listed on your Works Cited page

- Turn in your essay in an unreadable font, when the assignment clearly asks for 12 pt. Times New Roman (script-style fonts are especially frustrating)

- Summarize. -- I read it. I swear to you, I've read the text lots of times and I know what happens in it. An essay that does nothing but tell me the story all over again makes me wonder if you read it or if you're paraphrasing the summary on Sparknotes

- Use no formatting whatsoever. Throw in some quotes, with maybe some quotation marks at (either) the beginning or end of the quote. No page numbers. No author's name. No Works Cited page, or maybe one but just with a handful of internet links with no mention of what they actually are

- Misspell your own name

- Misspell, repeatedly and in various forms, the title of the work you are writing about

- Write, in the essay, that the text is old and boring and there is no point in anyone reading it anymore

- And, of course, plagiarize. -- Yes, we can tell when students plagiarize. We can usually tell when it's accidental. We can certainly tell when a friend in a different class or at a different school wrote it for you or gave you one that had already gotten a decent grade, because it will include things we didn't read or ever cover or will be in a style wholly unlike everything else you wrote for class. Also, when you cut and paste things from the internet, it is a good idea to make sure that you've changed the font type, size, and color to match the rest of the essay. The giant, purple, Comic Sans is a dead giveaway.

I think the idea for some students is that I have to grade it, so they might as well turn in something and see what happens, even if they know they don't care. I am shocked at how many of these students get their essays back and are delighted with the D, or shrug at the F, and figure it was worth the hour or so they spent cranking out something that should have taken 10 hours. But do you really want the person grading your essay to be angry???

So if you want to see smoke coming out of my ears, try out a few things on the list.

* All of these have happened in essays I have graded. Some of them are rare, it is true. Some of them are alarmingly frequent.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Citing in the Text (for Graduate Students)

alternate title: RefWorks, EndNote, and EasyBib are for Chumps

If you were an English major or minor, you probably still have your handy MLA Handbook for writing research papers:

If you were an English major or minor, you probably still have your handy MLA Handbook for writing research papers:

Yours might be the fifth or sixth edition, which is silver. But you've learned how to thumb through it hunting for how to cite a book with multiple authors, or a single-authored article from a journal published semi-annually that uses continuous pagination through its volumes.

But you are now a graduate student in English, so it's time to upgrade. Give that dog-eared Handbook to your cousin who just went off to college, because it won't help you anymore. If grad school is where you're getting started in English, you might hang on to your Chicago Manual for the odd occasional use but give that APA away. We don't cite in text with dates, because a lot of the stuff we work with has hard-to-determine publication dates, and a lot of it is super old, and it's literature so it's eternal anyway, right? Our goal is not to talk about how recent something is, but rather to get our reader literally on the same page with us, and to share useful sources they may want for themselves. We're all about the page numbers. So new to grad school or new to English in grad school ...

you need this:

The MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing is how we format our literature papers in graduate school. (If you're not one of mine, check with your prof, who may prefer Chicago - in which case, God help you. The exception to MLA for me is if you've already spotted a potential journal for your seminar paper and it requires something besides MLA, in which case, you should go ahead and format your paper for whatever style sheet that journal prefers, which might be Chicago but also might be a mixture of MLA and their own idiosyncratic preferences). Some places want p. for page number, others just want the number. Do your best to get it as right as you possibly, humanly, can.

The biggest change in practice will be the fact that, with the exception of long poems, including early modern plays, all your citations will be as footnotes or endnotes. Poetry and early modern play line numbers will still be cited in text (ex.: act 3, scene 4, line 54 of a Shakespeare or Jonson play will be cited 3.4.54 right after the quotation, as usual). For everything else, you need footnotes or endnotes. You may do either, depending on what you prefer or what a publisher prefers (but it's pretty easy to reformat from one to the other). The really good news is that you can now do little explanatory notes and chatty bits that don't fit into your paper, like the crazy bit of info on the colors used in 17th century embroidery that you found while researching that you think is cool and you want to include it somewhere in your paper but it is only barely, tangentially, connected to your argument, so you can't weave it in to the main paper. Now you can include it, as a note (kind of like a btw in conversation or an aside in Shakespeare). These are not required, however. What's required are citations.

The MLA guide will show you how to cite everything in the world. Or, at least, it will get close. MLA has to keep updating because the texts we use keep changing. You can now cite an email, even a tweet. Each time MLA catches up to technology, there is a change and a new edition. Do your best to be current and to adapt the citation examples you see in the guide to the source you have in front of you. The guide may have an example for an essay by a single author from a collection with a single editor, and it may have an example for a book with multiple editors. If what you need to cite is a single-author essay from a collection with multiple editors, it's up to you to combine the two. Do your best. And make your decisions with an eye for making it as easy as possible for your reader to go get your source off a library shelf or online database, and turn exactly to the page on which your quotation appears. That is your governing principle.

If you've made it a practice to get by with resources like EasyBib, you're going to have to stop now, because EasyBib can't help you where you're going. Those resources will get you a partially accurate Works Cited page. They will NOT get you footnote or endnote citations. But do not fret. You can do this. And it's important that you know the parts of a citation, so that you know how to properly raid a bibliography for your own research.

If you're writing about literary texts that have multiple editions (Shakespeare!), the first notes you create will most likely be statements of which editions you used. The first time you refer to a primary text, you should create a note like this. Editions are different, especially for older texts that had multiple printings, so it's good for your reader to know up front whether you're using a Norton edition or a Bantam, or whether you're using an original printing of an old text:

After that first statement, you just do your regular, old, in-text citations for line numbers:

For all other literary texts for which we depend upon page numbers rather than line numbers (all prose, modern plays, etc.), you cite in a note:

After the first full citation, you just give the author or text and page number:

Secondary texts are treated similarly. The first citation has all the info and the subsequent ones give author and page:

In this last example, you see that note 8 is a little chatty. That's because the essay refers to encoded nationalism, but doesn't want to go into a thing about it, and so refers and interested reader to a useful source on the subject.

Okay, you've got it, right? Only, how does one actually make the formatting happen? (These instructions are for Microsoft Word):

Type the sentence you need to give a note for, and put your ending punctuation, and then make sure your cursor is immediately after that ending punctuation. Now move the cursor to References at your top toolbar,

and click on Insert Footnote:

which will give you this at the bottom of the page:

into which you type your citation:

When you're done, click the cursor back to the space just after the superscript note number in your main essay text and keep going.

That's it. Footnotes. They're awesome. They actually give you much more freedom in your writing - freedom to convey your argument to your reader without interruptions. You also, over time, gain a sense of the inner workings of citations and will become adept at reading citations and other footnotes for the information you actually want: who edited this? who published it? who are the major voices in this discourse? if this footnote is all a list of who has done work on this subject, which of these will be useful to me?

And you get to write notes for your readers with those things in mind, as well.

That's really it. Now go do it.

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Summary, Why It's Bad, and How to Avoid It

If you're writing for me, there's a good chance your assignment has some version of the following on it:

Do Not Summarize.

And if you'll look at the grading rubric I use (available on the Moodle course page) you'll see that summary appears in the lower grades and analysis appear in the higher grades. That's because summary might show that you read the text, but it also might show that you just read the online study guide, and all it shows anybody is what happens in the text rather than what the text means. An essay should show your reader something cool about the text that you've noticed, or should seek to answer a question about the text that you had when you started writing. An essay should not just churn through the stuff anyone who has read it already knows. That is boring to write and it sure is boring to read. Analysis lets you engage with the text and do something new and different, which is more interesting to write and absolutely more interesting to read. Summary proves that the text happened. Analysis proves that something going on in the text that might not be immediately obvious is really going on.

So how to avoid summary and make sure that what you're doing is analyzing?

The first step in this happens early in the writing, although it's possible to go back and fix summary later. But first and foremost, assume that your reader has also read the text or texts you're writing about. That means you do NOT tell the reader what happens or who the character is. The whole entire point of an English essay is to point out things the reader of the essay does not already realize. You may think that a teacher already knows every possible idea in a text, but that simply is not the case. My students surprise me every day with cool ideas I've never thought of before. You will have to remind me where you are, because I won't be in your head with you, but do this in the same sort of way you would if you and a friend were talking about a movie you just saw together. Can you imagine walking out of a movie theatre with someone and saying "So the first thing that happens is a girl, whose name is Mary, loses her job at a law firm. Then she meets a man at a coffee shop who falls in love with her at first sight." ?? No way, because your friend would stop you and say "Dude, I was there. I saw the same movie you did." What you'd do instead is say, "You know that part where she's walking out of the coffee shop and he follows her with his eyes? That was an interesting way to show that he falls for her on sight." The first example summarizes the movie's opening, and the second examples starts to analyze how the story shows instead of tells that the man fell in love.

The second step is to make sure you never give more than three consecutive statements about what happens without stopping to talk about meaning. Sometimes, particularly with a longer text, you'll need to give a few markers about the story in order to help the reader figure out where you are in it while you're talking. Never give more than three plot markers for each point you want to make. After all, you'll be providing a page number in your citation, anyway, so it's not like I can't figure it out on my own. If you want to make sure that I am with you on the fact that you're talking about the moment Aeneas realizes he has to leave Dido, you can tell me a couple of things leading up to that moment. But don't get carried away and just start telling me the story. Only give me the bare minimum to know one or two things leading up to that moment.

Don't just string quotes together, tell me what the quotes mean (more on that here: write4bates.blogspot.com/2013/06/how-to-quote.html) Just using quotations from the text does not mean you're avoiding summary if what you're giving me are a series of plot events in your own words with quotes inserted occasionally. I call these "quotey summaries" and they are particularly frustrating because I need to know what those quotes mean to you, not just that they are there. And telling me what happens before and after Dido's exact words of grief is not the same thing as taking a few sentences (at least) to point out what is interesting about the word choice in her cry, or why it's interesting that it happens when and where and how it happens.

Don't write your thesis statement first and then not look at it again while you're writing the rest of the essay. Look back at your thesis statement at the end of each paragraph and make certain that paragraph did something substantial towards proving the hypothesis suggested in your thesis statement. Every single paragraph in your essay needs to be a point towards proving your thesis. You cannot do this if you are summarizing. I read too many papers that offer at the beginning that a particular pattern in a text means something or other, and then seem to forget entirely what they are trying to prove as sit back and just re-tell the story like I've never read it before. Your thesis statement should suggest a way of understanding the text better, and then work in each paragraph to prove it.

Do not tell a reader what happens in a text. Tell your reader WHY it happens the way that it does.

Do Not Summarize.

And if you'll look at the grading rubric I use (available on the Moodle course page) you'll see that summary appears in the lower grades and analysis appear in the higher grades. That's because summary might show that you read the text, but it also might show that you just read the online study guide, and all it shows anybody is what happens in the text rather than what the text means. An essay should show your reader something cool about the text that you've noticed, or should seek to answer a question about the text that you had when you started writing. An essay should not just churn through the stuff anyone who has read it already knows. That is boring to write and it sure is boring to read. Analysis lets you engage with the text and do something new and different, which is more interesting to write and absolutely more interesting to read. Summary proves that the text happened. Analysis proves that something going on in the text that might not be immediately obvious is really going on.

So how to avoid summary and make sure that what you're doing is analyzing?

The first step in this happens early in the writing, although it's possible to go back and fix summary later. But first and foremost, assume that your reader has also read the text or texts you're writing about. That means you do NOT tell the reader what happens or who the character is. The whole entire point of an English essay is to point out things the reader of the essay does not already realize. You may think that a teacher already knows every possible idea in a text, but that simply is not the case. My students surprise me every day with cool ideas I've never thought of before. You will have to remind me where you are, because I won't be in your head with you, but do this in the same sort of way you would if you and a friend were talking about a movie you just saw together. Can you imagine walking out of a movie theatre with someone and saying "So the first thing that happens is a girl, whose name is Mary, loses her job at a law firm. Then she meets a man at a coffee shop who falls in love with her at first sight." ?? No way, because your friend would stop you and say "Dude, I was there. I saw the same movie you did." What you'd do instead is say, "You know that part where she's walking out of the coffee shop and he follows her with his eyes? That was an interesting way to show that he falls for her on sight." The first example summarizes the movie's opening, and the second examples starts to analyze how the story shows instead of tells that the man fell in love.

The second step is to make sure you never give more than three consecutive statements about what happens without stopping to talk about meaning. Sometimes, particularly with a longer text, you'll need to give a few markers about the story in order to help the reader figure out where you are in it while you're talking. Never give more than three plot markers for each point you want to make. After all, you'll be providing a page number in your citation, anyway, so it's not like I can't figure it out on my own. If you want to make sure that I am with you on the fact that you're talking about the moment Aeneas realizes he has to leave Dido, you can tell me a couple of things leading up to that moment. But don't get carried away and just start telling me the story. Only give me the bare minimum to know one or two things leading up to that moment.

Don't just string quotes together, tell me what the quotes mean (more on that here: write4bates.blogspot.com/2013/06/how-to-quote.html) Just using quotations from the text does not mean you're avoiding summary if what you're giving me are a series of plot events in your own words with quotes inserted occasionally. I call these "quotey summaries" and they are particularly frustrating because I need to know what those quotes mean to you, not just that they are there. And telling me what happens before and after Dido's exact words of grief is not the same thing as taking a few sentences (at least) to point out what is interesting about the word choice in her cry, or why it's interesting that it happens when and where and how it happens.

Don't write your thesis statement first and then not look at it again while you're writing the rest of the essay. Look back at your thesis statement at the end of each paragraph and make certain that paragraph did something substantial towards proving the hypothesis suggested in your thesis statement. Every single paragraph in your essay needs to be a point towards proving your thesis. You cannot do this if you are summarizing. I read too many papers that offer at the beginning that a particular pattern in a text means something or other, and then seem to forget entirely what they are trying to prove as sit back and just re-tell the story like I've never read it before. Your thesis statement should suggest a way of understanding the text better, and then work in each paragraph to prove it.

Do not tell a reader what happens in a text. Tell your reader WHY it happens the way that it does.

Sunday, June 23, 2013

I, You, We, He/She/They

(updated 3 May 2019 for gender pronoun inclusion)

I

You may use "I" when writing for me if you need to, but only if you need to. There is no need for the stuffy and convoluted "This author sees an important connection between war and cultural production." It's okay to write "I am convinced of an important connection between war and cultural production." What you don't want to do is weaken your statements with "I think" and "I feel" - "I think that Frodo is an anti-hero figure because he is small and inexperienced, and defies the norm of strength and skill in battle, but he has courage and compassion" sounds like you haven't made your mind up yet. Write it that way if it gets you where your going, but then go back and delete the weakening words "I think" so that you have "Frodo is an anti-hero figure because he is small and inexperienced, and defies the norm of strength and skill in battle, but he has courage and compassion." There. You're sure and you say so and now you can prove it.I

You

Use "You" if you are directly addressing your reader, and in no other circumstances. Please, in formal writing, do not use "you" to mean "one." To write "When you first go visit the Dean of Students' office you will probably be nervous" is much too casual. Instead, put the noun you actually mean: "When students first go visit the Dean of Students' office they are probably nervous." If you are trying to find a general, inclusive pronoun, use "we."

We

If the audience for your essay could reasonably be included in a "we," then use "we." Instead of "When anybody reads The Great Gatsby they are struck by the charm of the main character," or "When you read The Great Gatsby," etc. etc., try "When we read The Great Gatsby we are struck by the charm of the main character." It helps to create inclusiveness, and helps dodge some awkward pronoun gymnastics: "It is important that we recycle because the world cannot continue to replenish our natural resources at the rate at which we are using them."

He/She/They

When speaking in hypotheticals, we are first tempted to go for singular pronouns - perhaps this is a very human instinct to not overreach on something unproven. I don't know. I do know that using single pronouns for anything but determined, designated single nouns becomes tricky before you know it. Example: "When a student goes to visit the Dean's office he or she may find that he or she is nervous about the outcome of his or her visit."* Terrible. Clunky and awful. No one wants that. And so too often we avoid the he/she stuff by turning to a plural pronoun there - they. Our example becomes: "When a student goes to visit the Dean's office they may find that they are nervous about the outcome of their visit." But this is incorrect because the original pronoun was singular, unless "they" is the preferred pronoun of the person being referred to.

If you know the preferred pronoun of the person, use it. I, for example, prefer she/her. So if you're talking about me going somewhere, say "When the professor goes to see the Dean's office, she may find that she is nervous about the outcome of her visit." (I'm not, though - I love my Dean.) If you know that the person you're referring to prefers he/him, use he/him. If you know that the person has asked for they/them, then please use they/them. In that situation, they/them is correct. If we are referring to a student who is, perhaps, transgender and has requested the they/them pronouns, we would write, "When the student goes to visit the Dean's office they may find that they are nervous about the outcome of their visit." Although, again, they have no reason to be, because the Dean is delightful.

But, often the issue is that we are writing about a hypothetical person, or people. In such a case, make the original noun plural, and you're all set. Fixed example: "When students goes to visit the Dean's office they may find that they are nervous about the outcome." (The end got tricky, because I had to make it "their visit" which looks like they're all visiting at once, or make it "their visits" which could mean that they each visit multiple times, heaven forbid. So I just dropped it since it wasn't strictly necessary).

*A bit of history: There was a time, dear students, which you will not remember because it was approximately well before you were born, when people in groups were referred to as male if there any men in the group at all. When I was in college, all students, in all brochures and handbooks, were referred to as he, him, his, etc. This was not if anyone was referring to a specific female student, of course, but when talking about a typical, hypothetical student, they would say or write male pronouns. It was this way in all Western communication (business, government, etc.) and had been that way for pretty much ever. A brochure from my college, or from a church or company or organization, would read something like this: "Any student wishing to consult with his advisor should contact his advisor directly" or "Any member wishing to upgrade his membership should consult the guidelines" or "If an employee must take extra sick days he should discuss this with his supervisor." That was just life. (I had friends at all-girls colleges like Agnes Scott, where this was not the case, who said it was a relief to finally hear themselves referred to as she, her, and hers). A cultural movement in the early 1990's, generally called "Political Correctness," worked to change this, along with eliminating official terminology that doubled as discriminatory slurs (all disabled people used to be labeled "retarded" - officially - and I'm not kidding about that). Political correctness was deeply hated at the time and still is by some, and it was a huge mess getting a cultural consensus around how to use language both effectively and respectfully. We went through some awkward times when we had to write "he or she" each time we used a hypothetical. It took us a while to get around to plurals. I say all this because it really is that important that we get our pronouns right, because in this case "right" means "respectful to the existence of other human beings." Political correctness accomplished wonderful things, not the least of which is college brochures that acknowledge female students along with male ones.

Friday, June 21, 2013

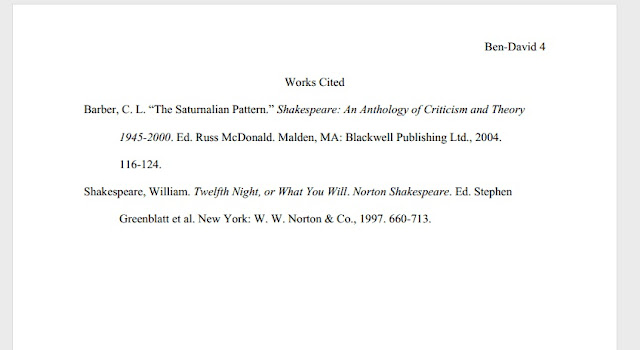

The Works Cited Page

The Works Cited page is a page which lists, in MLA format, the works which were cited in the essay. I reiterate: the works WHICH WERE CITED IN THE ESSAY. All of them. And nothing else. In alphabetical order, because it's neat and tidy and because it's not hard to alphabetize things.

If you need help with MLA format and you can't figure out how to use your printed MLA guide, you can use the very helpful OWL site from Purdue's Writing Center:

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/01/

Too often the Works Cited page does not match up with the works used in the essay, and this is frustrating for the teacher grading the essay and disappointing for the student when the essay comes back with huge points taken off.

Use the MLA guide to format your citations. RefWorks and OneNote and online formatting things which have you enter the ISBN number and then generate your citation for you are too often wrong. Best to do it yourself. If you are absolutely helpless at this, consider doing it yourself and then double checking using WorldCat's formatting (make sure you set it to MLA), which I have often found to be correctly done.

EVEN IF YOU ARE USING ONLY ONE OR TWO TEXTS (in, say, a critical analysis essay which is a close reading of a single text) YOU ALWAYS CITE ANY AND EVERYTHING YOU QUOTED IN THE ESSAY.

If all you have is a single source, and there is plenty of room at the end of the last page of your essay for it, you do not have to start a whole new page for just one citation, you can just hit Enter a few times to make some space and then tack the one citation on at the end.

If you need help with MLA format and you can't figure out how to use your printed MLA guide, you can use the very helpful OWL site from Purdue's Writing Center:

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/01/

Too often the Works Cited page does not match up with the works used in the essay, and this is frustrating for the teacher grading the essay and disappointing for the student when the essay comes back with huge points taken off.

Use the MLA guide to format your citations. RefWorks and OneNote and online formatting things which have you enter the ISBN number and then generate your citation for you are too often wrong. Best to do it yourself. If you are absolutely helpless at this, consider doing it yourself and then double checking using WorldCat's formatting (make sure you set it to MLA), which I have often found to be correctly done.

EVEN IF YOU ARE USING ONLY ONE OR TWO TEXTS (in, say, a critical analysis essay which is a close reading of a single text) YOU ALWAYS CITE ANY AND EVERYTHING YOU QUOTED IN THE ESSAY.

If all you have is a single source, and there is plenty of room at the end of the last page of your essay for it, you do not have to start a whole new page for just one citation, you can just hit Enter a few times to make some space and then tack the one citation on at the end.

How to Use Quotations from the Text

Respond to Your Quotes!

Select a quote that you can respond to, not something that you think says everything that needs to be said. Those quotes are boring conversation stoppers. You want ideas that you can comment on. Even something that you think is the end all, be all is something you can comment on. Find a quote that says "The Tempest is Shakespeare's last play because it is his most definitive play," and you can follow that with a discussion of what "definitive" could mean in the canon of a prolific writer and what about the play may or may not be definitive.

Example:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101). Music was also very important in this culture, as was weaving.

BAD. BAD. BAD.

Instead, respond to every single quote, always and forever, by doing the following three things:

1. Restate the quote in your own words, because it's dangerous to assume that your reader is getting the same thing out of it that you are. This is an opportunity to explain terminology or vocabulary being used by your source that your reader might not know, as well as any context from the source that isn't in the part of the text you chose to quote.. Use at least one sentence for this.

2. Discuss the quote - respond to it with your own thoughts. What is interesting in the wording, or the details? Unpack the quote. Use at least one sentence.

3. Tie what you've now discussed back to your thesis from your introductory paragraph, which in this example, we'll say was an argument that while Beowulf is a Germanic tribe story from a pre-chivalric medieval culture, it was transcribed by someone in a chivalric culture and so was reshaped to fit that culture's preferences.

new example:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101). What Lynn is pointing out here is that the tenets of the chivalric code, like a respect for the honor of one's opponent, existed beyond tournaments and could also be found in battle. It is interesting to note that this was between "aristocratic knights," indicating that fighters from other social classes may not have felt held to the same standards, or at least could not expect to find them extended to themselves. This may explain differences in Beowulf's treatment of fellow knights when compared to the monsters he fights - he does not perceive Grendel or the dragon to be honorable opponents, and so does not perceive himself bound to a chivalric code when fighting them.

The second use of the quote actually puts the quote to work for the argument, whereas the first lets the quote just sit there, lazy and unhelpful. And besides, the first use has 52 words; the second has 157. Any time students come to me and says they are having trouble reaching the word count minimum, I can just about go to the bank on the fact that they haven't fully discussed their quotes. Do this for every single quote and you can't help but have a rich, developed, complete essay.

Introduce Your Quotes!

Always, always, always. Failing to do so sends me into a frenzy, and it's so easy to do it correctly.

Instead of this:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101).

Do this:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101).

It is, after all, polite to introduce people to each other. "Reader, meet John Lynn, author of a book about battle and combat."

After the first introduction, we're all on a chummy, last-name-basis, so you can just call him Lynn.

Lynn goes on to argue that "Claims that an enemy army displayed cowardice in the field can be an insult or a misperception more than a careful evaluation" (287).

Cite Your Quotes Correctly!

Use MLA style parenthetical citation.

Prose, like novels or non-fiction, get page numbers, as do modern plays, and any journal article. Just make sure you're very specific later on your Works Cited page about which edition you used, since page numbers can be different from edition to edition. If you used a Kindle, see MLA for how to cite sections. Just put the page number(s) from your quote in parentheses, and you're done. See the John Lynn quote above for an example. Simple.

Poetry gets line numbers. If your edition doesn't give you line numbers in the margin, I'm afraid you'll just have to count them for yourself. Then put the line numbers in parentheses at the end of the quote. Also for poetry, you must separate lines with / marks, unless you have 4 or more lines in a row, in which case you should block quote. This is also true for plays that are in poetic form, like early modern plays by Shakespeare and others. The illustration below shows both: first, a block quote, and then, in the discussion of that quote, lines separated by a mark:

Note that the block quote is double indented, and that it is introduced by "In Cymbeline, the lines are:".

Note also that, for Shakespeare, as for any 5 act play, we do not give page numbers, we give act, scene, and line numbers, and we give them in Arabic numerals. There once was a time when this was done thus (Act V, scene V, lines 559-565), but then MLA realized that was cumbersome and unnecessary, and shortened it to (V.V.559-565), and then realized Roman numerals were not necessary, and so it is now the nice, easy-to-write-and-read (5.5.559-565)

Select a quote that you can respond to, not something that you think says everything that needs to be said. Those quotes are boring conversation stoppers. You want ideas that you can comment on. Even something that you think is the end all, be all is something you can comment on. Find a quote that says "The Tempest is Shakespeare's last play because it is his most definitive play," and you can follow that with a discussion of what "definitive" could mean in the canon of a prolific writer and what about the play may or may not be definitive.

DO NOT QUOTE AND THEN MOVE ON TO ANOTHER IDEA.

TO DO SO IS A QUOTE HIT-AND-RUN AND IT IS ILLEGAL IN ALL ESSAYS FOR ME.

Example:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101). Music was also very important in this culture, as was weaving.

BAD. BAD. BAD.

Instead, respond to every single quote, always and forever, by doing the following three things:

1. Restate the quote in your own words, because it's dangerous to assume that your reader is getting the same thing out of it that you are. This is an opportunity to explain terminology or vocabulary being used by your source that your reader might not know, as well as any context from the source that isn't in the part of the text you chose to quote.. Use at least one sentence for this.

2. Discuss the quote - respond to it with your own thoughts. What is interesting in the wording, or the details? Unpack the quote. Use at least one sentence.

3. Tie what you've now discussed back to your thesis from your introductory paragraph, which in this example, we'll say was an argument that while Beowulf is a Germanic tribe story from a pre-chivalric medieval culture, it was transcribed by someone in a chivalric culture and so was reshaped to fit that culture's preferences.

new example:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101). What Lynn is pointing out here is that the tenets of the chivalric code, like a respect for the honor of one's opponent, existed beyond tournaments and could also be found in battle. It is interesting to note that this was between "aristocratic knights," indicating that fighters from other social classes may not have felt held to the same standards, or at least could not expect to find them extended to themselves. This may explain differences in Beowulf's treatment of fellow knights when compared to the monsters he fights - he does not perceive Grendel or the dragon to be honorable opponents, and so does not perceive himself bound to a chivalric code when fighting them.

The second use of the quote actually puts the quote to work for the argument, whereas the first lets the quote just sit there, lazy and unhelpful. And besides, the first use has 52 words; the second has 157. Any time students come to me and says they are having trouble reaching the word count minimum, I can just about go to the bank on the fact that they haven't fully discussed their quotes. Do this for every single quote and you can't help but have a rich, developed, complete essay.

Introduce Your Quotes!

Always, always, always. Failing to do so sends me into a frenzy, and it's so easy to do it correctly.

Instead of this:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101).

Do this:

Chivalry was a standard of behavior for all of life but was connected to warfare. John Lynn states in Battle: A History of Combat and Culture that "In combat between aristocratic knights, the code of chivalry could very much apply" (101).

It is, after all, polite to introduce people to each other. "Reader, meet John Lynn, author of a book about battle and combat."

After the first introduction, we're all on a chummy, last-name-basis, so you can just call him Lynn.

Lynn goes on to argue that "Claims that an enemy army displayed cowardice in the field can be an insult or a misperception more than a careful evaluation" (287).

Cite Your Quotes Correctly!

Use MLA style parenthetical citation.

Prose, like novels or non-fiction, get page numbers, as do modern plays, and any journal article. Just make sure you're very specific later on your Works Cited page about which edition you used, since page numbers can be different from edition to edition. If you used a Kindle, see MLA for how to cite sections. Just put the page number(s) from your quote in parentheses, and you're done. See the John Lynn quote above for an example. Simple.

Poetry gets line numbers. If your edition doesn't give you line numbers in the margin, I'm afraid you'll just have to count them for yourself. Then put the line numbers in parentheses at the end of the quote. Also for poetry, you must separate lines with / marks, unless you have 4 or more lines in a row, in which case you should block quote. This is also true for plays that are in poetic form, like early modern plays by Shakespeare and others. The illustration below shows both: first, a block quote, and then, in the discussion of that quote, lines separated by a mark:

Note that the block quote is double indented, and that it is introduced by "In Cymbeline, the lines are:".

Note also that, for Shakespeare, as for any 5 act play, we do not give page numbers, we give act, scene, and line numbers, and we give them in Arabic numerals. There once was a time when this was done thus (Act V, scene V, lines 559-565), but then MLA realized that was cumbersome and unnecessary, and shortened it to (V.V.559-565), and then realized Roman numerals were not necessary, and so it is now the nice, easy-to-write-and-read (5.5.559-565)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)